Whether I’m working with kids, teens, or adults, as I’ve done for the past 10+ years, I always see a look of panic in the students’ eyes when they see their rhythms going up and down.

It always leads to a good conversation about note stem direction and the rules that go along with it.

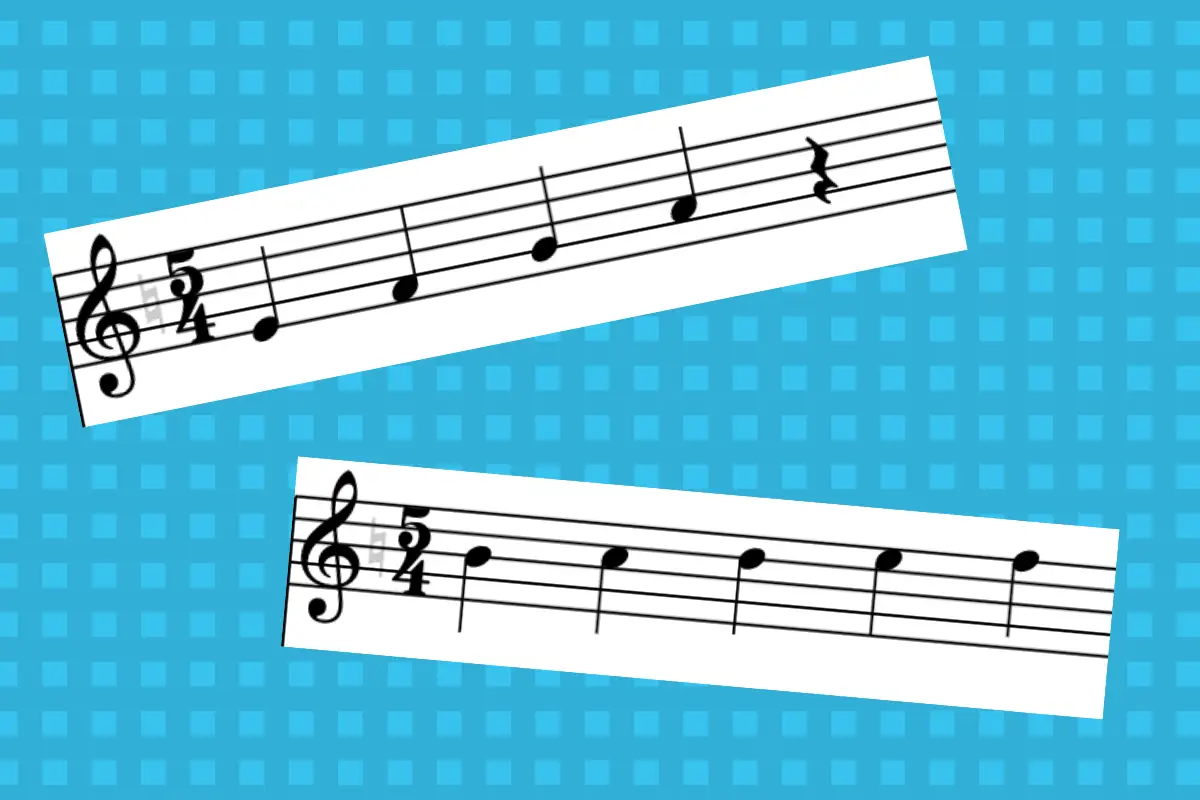

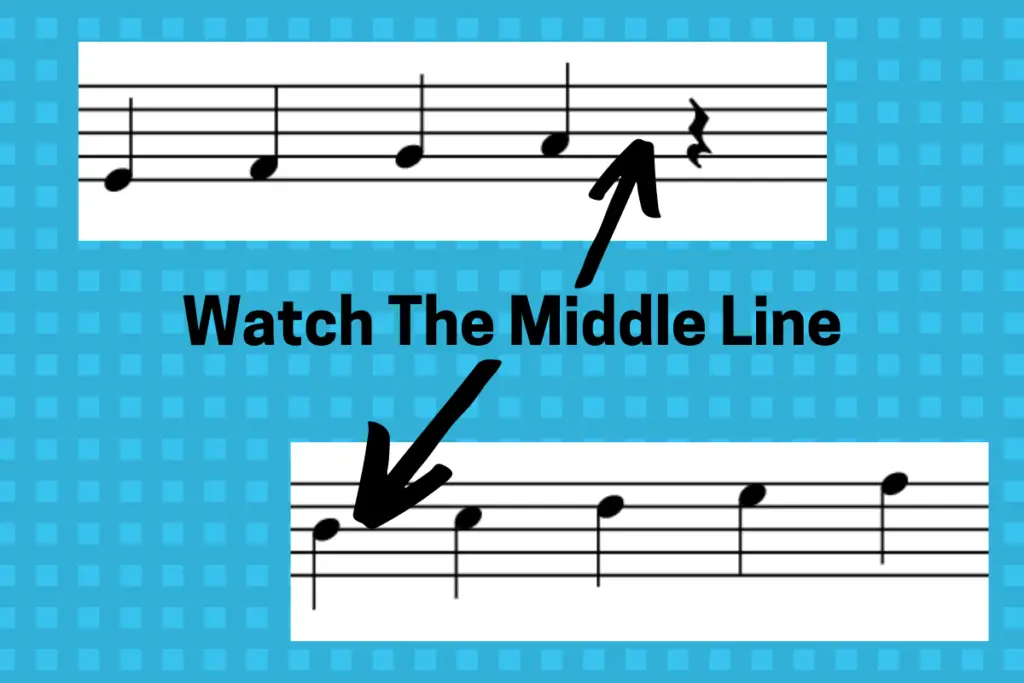

Note stem direction changes based on where the note lies on the musical staff. If the note head is on the middle line or above, the stem goes upside down. If the notehead lies on the second space from the bottom or down, the stem goes up.

This is largely to save space and make the music easier to read, and it doesn’t impact the length of the note at all.

But knowing the correct stem direction is key in making easier-to-read notes.

Of course, the rules aren’t as cut and dry as I stated above, so read ahead for the details and exceptions.

Table of Contents

The Main Note Stem Direction Rule

The correct direction of the stem depends on the position of the notes.

In music, the name of the game is to save space when printing and make things easier to read.

Believe it or not, we don’t aim to make things harder for you.

If we kept the stems going up on the notes all the time, the higher you play, the harder it would be to read, and the more space your music would take up.

By flipping the notes upside down, we save space as the notes climb into the upper register.

The opposite direction is also true with low notes.

This leads to the main rule of note stems:

From the third line on the staff and above, the stems on a single note go down. From the second space from the bottom and below, the note stems go up.

This rule holds true no matter what clef you use, be it a treble clef, bass clef, alto clef, or tenor clef.

The image at the beginning of this section shows this well, but if you want to know the specific notes for each clef, check out this chart.

| Clef | Stems going down | Stems going up |

|---|---|---|

| Treble Clef | B, C, D, E, F… | A, G, F, E… |

| Bass Clef | D, E, F, G, A… | C, B, A, G… |

| Alto Clef | C, D, E, F, G… | B, A, G, F… |

| Tenor Clef | E, D, C, B, A… | G, F, E, D… |

Note Stem Direction In Split Parts

The other main rule to know for the stem direction of the note is around when you have split parts.

If there are multiple parts on a single staff, such as with piano at times or in most choral pieces, you’ll see multiple melody notes on the staff at the same time.

In this case, stem direction rules work in different ways.

For choral works, stem direction follows these rules:

- Soprano part = Stem up on the treble clef

- Alto part = Stem down on the treble clef

- Tenor part = Stem up on the bass clef

- Bass part = Stemd down on the bass clef

The lower voices in each clef go down, and the upper voices in each clef go up.

It almost makes this special rule always the opposite of what it’s supposed to be normally.

This is obviously to make the music easier to read.

If they followed the normal rules, there would be collisions everywhere!

The piano always has split parts too, the right hand and the left hand.

Most of the time, the right hand will be on the treble clef, and the left hand is on the bass clef.

But if the parts get too close together, this has to change.

If the piano parts end up right next to each other, the right hand has the stems going up, and the left hand has the stems going down.

Note Stem Rule About A Beamed Group (Grouped Notes)

A more complex set of music notation rules must be applied when you’re looking at a group of music notes connected by bars (such as eighth notes, sixteenth note, etc.).

The note stems can be connected, but the noteheads may travel above and below the middle line.

So which way does the stem go?

This rule requires two steps to figure out, and they need to be answered in this order.

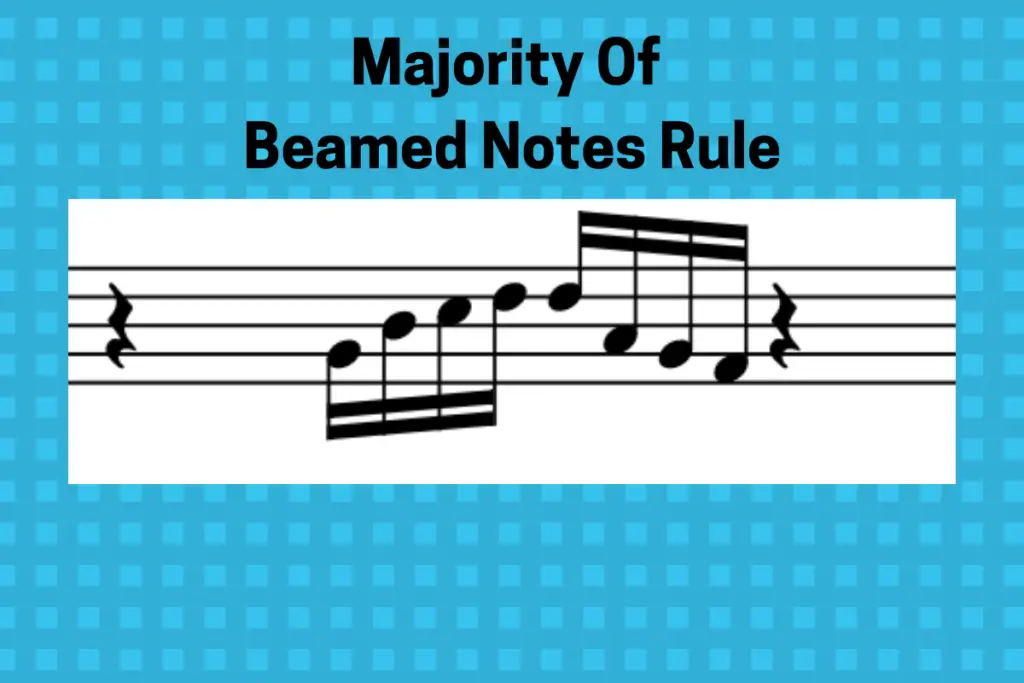

1. Follow the rule of the majority of notes in the group.

If you have a group of 4 eighth notes and 3 of them are below the middle line, all the stems go up.

The opposite is also true as the following example shows.

But what happens if they’re the same?

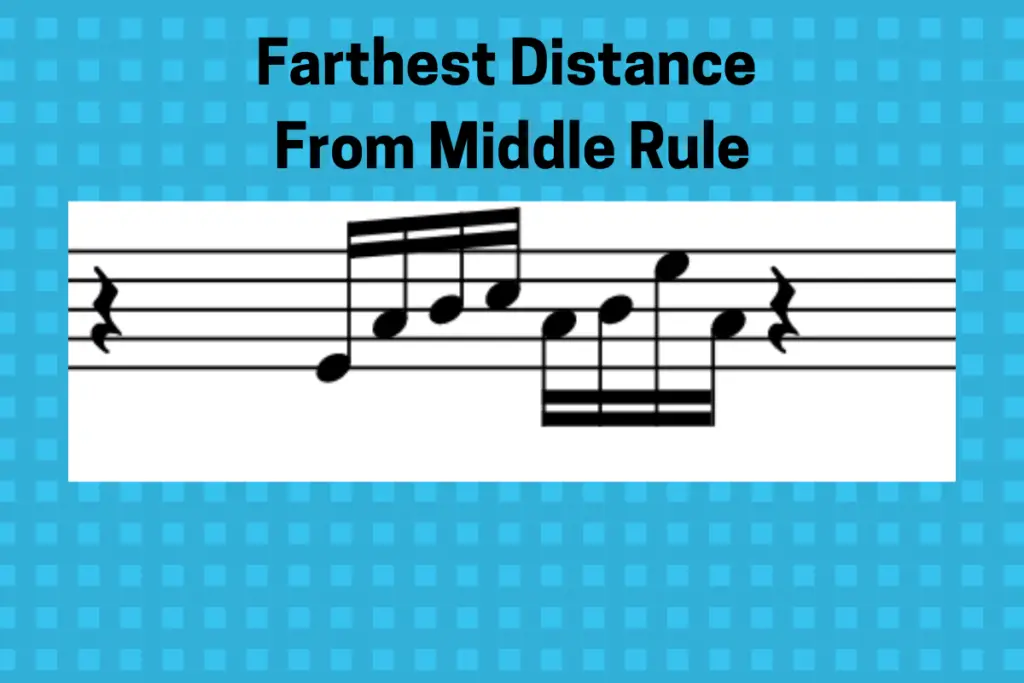

2. If the number of notes in a group is equal above and below the middle line, go with the rule of the note farthest from the middle.

If you have a group of 4 eighth notes in treble clef playing low E-low F-B-C, then you make the stems go up as the low E is farther from the middle line than the C.

What happens if both rules are equal?

Then, it’s a judgment call, though most standard notation programs will default to a downward stem.

Individual notes, such as a quarter note, aren’t affect by this rule.

How Long Are Note Stems?

The general rule for note stem length is that they’re drawn to cover and octave (about three and a half spaces). If the notes go farther than two ledger lines above and below the staff, the stem is drawn to meet the middle line of the staff.

This makes it easier to read.

Commonly Asked Questions

What Notes Have Stems?

All rhythmic values and notes have stems except a whole note.

Whole notes are notated as a circle and have no stems, therefore you don’t need to know any of the rules for this note value.

Is B Stem Up Or Down?

Some folks remember that high notes have downward stems and lower notes have upward stems, but they forget the middle line rule. If it’s on the middle line in any staff (including B), the stem goes down.

It’s fine if it goes either way, but traditionally it goes down.

There is no real reason for this other than it is what has become the standard.

Why Do Some Notes Have Two Stems?

If a note has two stems (split stems), it means there are two voices or parts playing in the same space. In this case, the two parts are split between either two people or half the section playing one and half the section playing the other.