Music symbols are many and varied. After all, music is a complex topic.

As a musician and music teacher, I’m often asked by people I play with what specific symbols mean.

One of my favorite ones to talk about is the squiggly line in music because it could mean 5 different things!

The squiggly line in music is used to refer to different things depending on how it appears in music and what style of music you’re playing. The five common uses include:

- Arpeggiated chords

- Mordents

- Trills

- Glissandi

- Strumming the guitar (for classical guitar)

Let’s talk about each of these with examples of what they look like and what to do when you see them.

Need some help on piano? Check out Flowkey with their easy-to-follow lessons and literal thousands of songs with learning tools.

I’ve been playing music for almost 20 years now, and I still use it to help me learn new songs (and it’s fun too!).

Table of Contents

Table Of Squiggly Line Symbol In Music And What It Means

For a quick reference, take a look at this table which includes an image example of the symbol, what it is, and what you do when you see it.

Of course, there are many nuances to how each of these should be performed, but these are general rules which will get you 90-95% of the way there.

| Symbol | Name | What You Do |

|---|---|---|

| Arpeggio | Play each note one at a time bottom to top |

| Mordent | Alter with the note above or below one time |

| Trill | Rapidly alternate with the starting note and the one above it (end on the starting note) |

| Glissando (Gliss) | Play all notes chromatically starting where the squiggle starts and moving up to the end note |

| Strum guitar (Classical) | In classical guitar, this means to strum all notated pitches rather than play them one at a time |

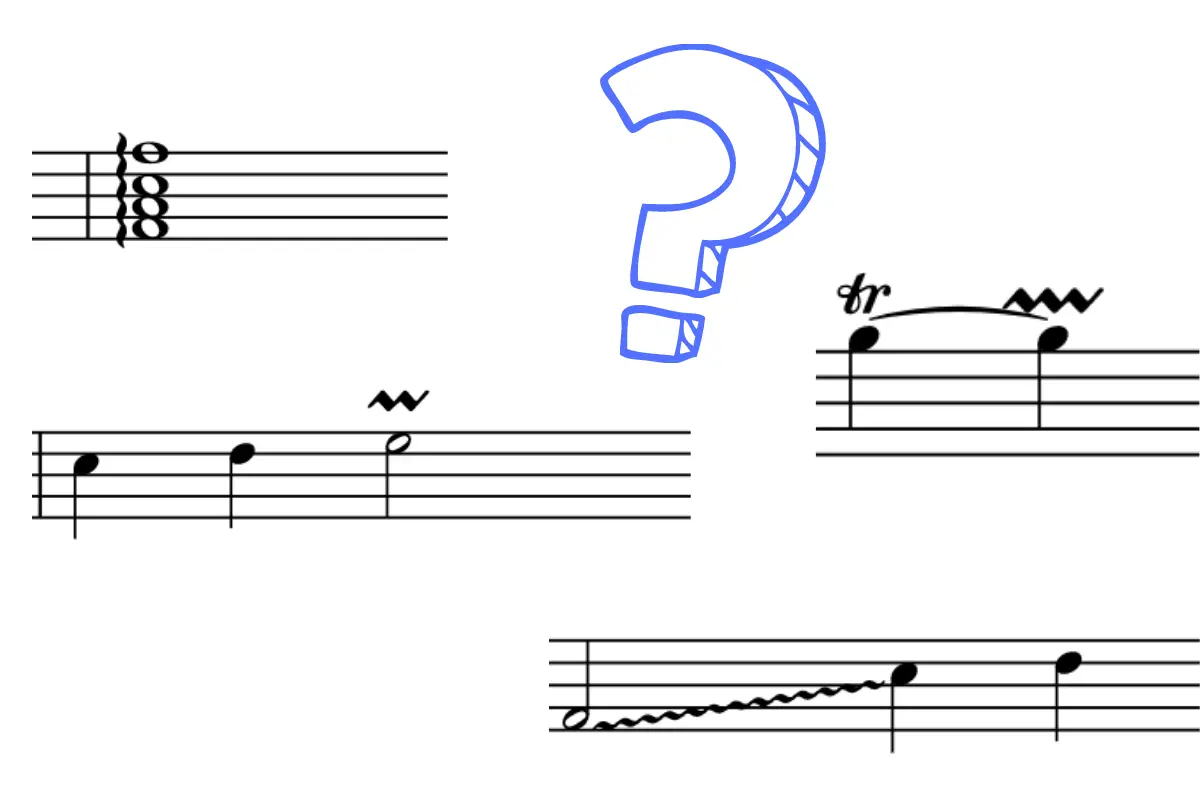

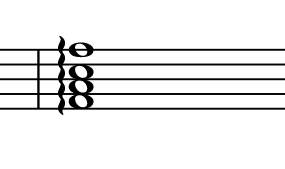

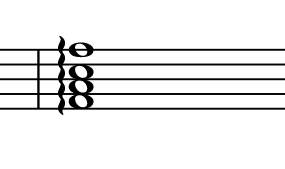

Squiggly Line In Music: Arpeggiated Chords

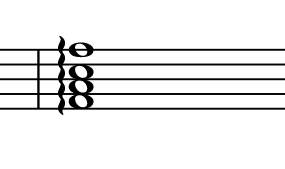

When you see a chord for piano or other keyboard instruments with a vertical squiggly line, this means you need to arpeggiate or spread the chords.

This is also called rolled chords or a broken chord for piano music.

When you play the chord, you usually start at the bottom and work your way quickly to the top.

Of course, not every arpeggiated chord should be played quickly or even from bottom to top.

For speed, the difference largely depends on the tempo of the piece of music.

If you’re playing anywhere from medium to fast tempi, a rapid sequence for the arpeggio is called for.

But if the tempo is slow or you’re approaching the end of a period or consequent phrase, some artistic expression in slowing down the notes may be called for.

By the way, click the link for our detailed article on antecedent and consequent phrases in music.

The direction aspect of the wavy line for arpeggios is a little different.

The vast majority of the time, you’ll play from the bottom to the top.

If you simply see a wavy line, you play from the bottom to the top.

However, if you see a down arrow at the bottom of the squiggle, this is your sign to play the arpeggio, starting at the top and moving toward the bottom.

Sometimes composers or transcribers will use up arrows (especially if they had to use a down arrow one), but this is rare.

Note: This marking is used almost exclusively for piano and keyboard instruments to achieve a harp-like effect.

Need some help on piano? Check out Flowkey with their easy-to-follow lessons and literal thousands of songs with learning tools.

I’ve been playing music for almost 20 years now, and I still use it to help me learn new songs (and it’s fun too!).

Example Of Arpeggio In Music

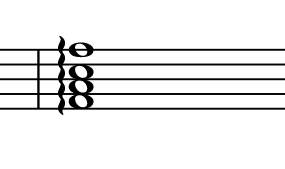

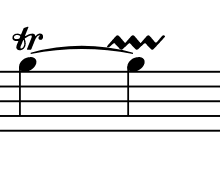

Mordent (A Short Squiggle)

A mordent is a short squiggle just above the note.

These musical symbols are like a mini-trill, as it were.

When the musician sees this musical symbol, they alternate between two notes one time rapidly.

For example, if a pianist sees a mordent above an E (in the key of C), they’ll come to the note and play E-F-E in rapid succession.

The goal is to be quick and precise here. It seems simple, but to pull it off well takes some practice.

You still want to keep the tempo and timing of the rhythm in line with the rest of the measure.

Newer players will often lose this feeling as they get too focused on the mordent itself.

Mordents (and many of these wavy lines in music) are ornamentations, and as such, they should only enhance the core of the music.

Mordents aren’t as common in music past the classical period and the baroque period.

J.S. Bach was famous for using mordents throughout his works, often with church vocals and harpsichord or organ.

There are two main types of mordents:

- Upper mordent

- Lower mordent

When you play a lower mordent, you alternate with the pitch below the written pitch.

So in the E example from earlier, a lower mordent goes E-D-E.

Lower mordents look like the normal mordent symbol but with a line through it.

Remember, as long as the overall flow and tempo of the measure and phrase stay consistent, you do have some creative choice in exactly how quickly you play the mordent.

An upper mordent is what we described above; often, it’s just called a mordent because the upper variation is more common.

Some people call mordents “shakes” in music, and if you think about it, it makes perfect sense.

Other Reading: Donating A Piano Guide

Example Of Mordent In Music

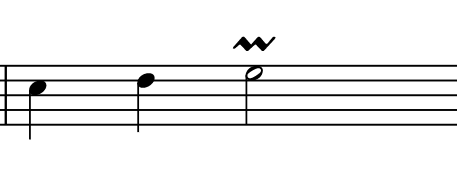

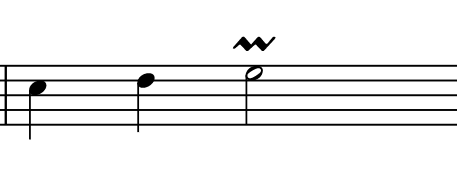

Trill

If you see the wavy line in music stretching over a note for longer than a single wave like a mordent, you need to play a trill.

It’s also notated with a short “tr.” in many cases.

As with the mordent, we need to rapidly alternate with the note next door in the key, usually the upper one.

But unlike the mordent, we play as many of the alternations as fast as possible during the length of the note while staying in tempo (unless it’s at the end of a piece with a rallentando or ritardando slowing down tempo mark).

Of course, my musician friends are freaking out a little right now.

As fast as possible? That’s all the direction you’re going to give?

Yes. Simply landing on the starting note for a moment, alternating as quickly as possible, and then landing on the starting note again for a moment before moving on gets you 90-95% of the way there.

In most music, no one will really care or notice any nuance of a trill.

But at the highest levels of music, there are some slight differences in how you play a trill depending on the marking, musical period, and even the composer.

For more on that, check out Classical Music’s article on trills.

The majority of the time, a trill alternates with its upper neighbor.

In modern music, you want to start with the main note and switch like crazy.

Many teachers love to use the example of playing as if your fingers were being electrocuted and forced to alternate at an inhuman rate.

I always found that analogy a bit morbid, but with young players, it seems to do the job.

In older styles of music, Classical music and Baroque music primarily, you actually start the trill on the note above the main one. You also may want to start slow and then alternate faster as time goes on.

Take some artistic license here.

Example Of Trill In Music

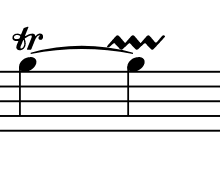

Glissando

If you see a squiggly line in sheet music stretched between two notes or starting on one note or starting in white space and then landing on a note, you need to play a glissando.

Glissandi are a blast to play and one of my favorite markings. That probably says a lot about me as a musician!

In a glissando, you play all notes chromatically between your starting pitch and ending pitch.

The goal is to hit the ending pitch at the exact moment the rhythm and tempo tell you to.

If there is a starting pitch written, hit it just long enough to get a feeling for it and then move on.

Most of the time, you want to finger or play through each note quickly.

You’re aiming for a sliding effect, where there’s no clear pitch as you slide from one note to another.

If no starting note is given, start on the note near where the marking starts on your staff.

Often, composers, transcribers, and arrangers will also give you hints as to when you start the gliss (as it’s called for short) by picking a specific spot for the line to begin.

If possible, match the marking as much as possible.

It’s said that only slide instruments, like the trombone, are the only instrument capable of giving a true glissando.

This is sort of true! It’s one of the things that makes the trombone so iconic.

I would add vocal glissandi in there as well, though it’s not as common to gliss on voice (although I did it recently in a concert).

Most of the time, glissandi come from below and move up, but some will come from above.

The marking will tell you which way to go.

Example Of Glissando In Music

Strum The Guitar

When you see a vertical squiggly line over several notes (like we did with arpeggiated piano chords) and you’re playing classical guitar, it’s time to strum those notes.

This may seem weird to most folks. Don’t we already strum guitars?

Classical guitar is a whole other style of music.

Almost everything about this style is different from the instrument (nylon strings, wider neck, more fingerpicking) to the music itself.

The normal for the Classical Guitar is to pick individual notes or a couple of notes at a time.

Strumming is the abnormal for this style, so it needs its own special marking.

In this case, it’s the same vertical squiggly line as before with the piano.

If the guitar sees all the notes stacked with no line, it means we need to strum quickly, in one motion.

When we see the vertical line (especially at a slower tempo), it means we need to strum more deliberately, almost like how a piano arpeggiates its chords.

Example Of Strumming On Classical Guitar

Need some help on piano? Check out Flowkey with their easy-to-follow lessons and literal thousands of songs with learning tools.

I’ve been playing music for almost 20 years now, and I still use it to help me learn new songs (and it’s fun too!).